The East African Legislative Assembly on Wednesday passed a motion calling on partner states to legally recognise the right to food and take urgent action to combat rising hunger and malnutrition across the region.

The motion, moved by South Sudanese lawmaker Woda Jeremiah, urges governments to integrate the right to adequate food into national development plans, abolish non-tariff barriers that restrict food movement, invest in climate-resilient agriculture, and expand social protection for vulnerable communities.

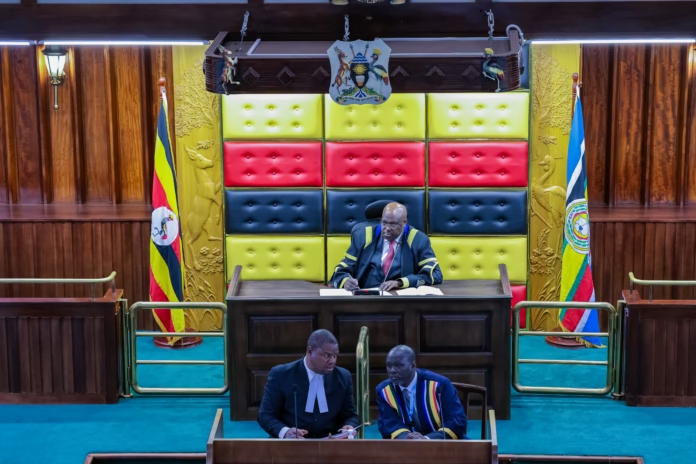

“The right to adequate food is not merely a humanitarian concern. It is a constitutional and political commitment,” Jeremiah told lawmakers during the sitting in Kampala. “It is really a shame when we say we are leaders, but we are leading hungry people or hungry communities. Let this Assembly be the voice that transforms aspiration into access, and resolutions into policy.”

The right to food was first recognized in Article 25 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which states that everyone has a right to a standard of living adequate for their health and well-being, including food. It became legally binding in 1976 under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

The U.N. Committee responsible for interpreting that covenant says the right is realised when every person has physical and economic access “at all times to adequate food or means for its procurement.”

Woda Jeremiah said East African countries remain off track in meeting food security targets despite legal commitments and the region’s agricultural potential. “Most of our children have stunted growth, and our young girls and women are anaemic. Our region is suffering from hunger, though it is bestowed with fertile agricultural lands,” he said. She cited South Sudan, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Kenya and Uganda as the most affected.

Official EAC data shows that food insecurity in the region is driven by climate shocks, conflict, rapid population growth and rising food prices, with women and children being the most vulnerable. The EAC Regional Food and Nutrition Security Strategy warns that weak policy harmonization, limited data systems and insufficient social safety nets are slowing progress.

Jeremiah pointed to some positive trends. Recent statistics under the EAC Integrated Statistical Strategy show increased crop production between June 2023 and June 2024, along with growth in livestock and fisheries between June 2024 and June 2025. “These developments have made a constructive contribution to the region’s overall food security landscape,” she said, while stressing that the region remains far from achieving its goals.

The adopted resolution invokes Article 49(2) of the EAC Treaty and recommends that partner states ensure legal recognition of the right to food, implement policies that support nutrition education and land access, invest in soil restoration and climate-resilient farming, eliminate export bans and non-tariff barriers to stabilize food markets, and expand school feeding and social protection programs.

Ugandan lawmaker Paul Musamali supported the motion, warning that food insecurity could trigger political instability if not addressed. “There is no debate about it food security is about our lives,” he said. “East African states should take it very seriously because we are just lucky. In East Africa, even the birds can plant seeds and they grow.”

Musamali cited Sudan as an example of how food shortages can fuel unrest. “We are aware that the government in Sudan was overthrown because there was no bread in Khartoum,” he said. “If we don’t handle the issue of food seriously, we can create a lot of insecurity and instability in our states.”

Jeremiah told the Assembly that member states must ensure effective oversight and proper resource allocation so that no East African goes hungry. “Our leadership on this issue lays the foundation for a future where dignity is upheld and no citizen is left behind,” she said.